A pair of hitmen find themselves conflicted when their latest target dies gripping the photo of an innocent-looking nurse. Who was this man, what’s his relationship to the woman in the photo, and why did he have to die? Asking questions is taboo when you’re a hired killer, and you’re probably better off not knowing anyway, but there’s something that’s bugging veteran executioner Joji (Jo Shishido) and it’s not just the missing 20 million dollars.

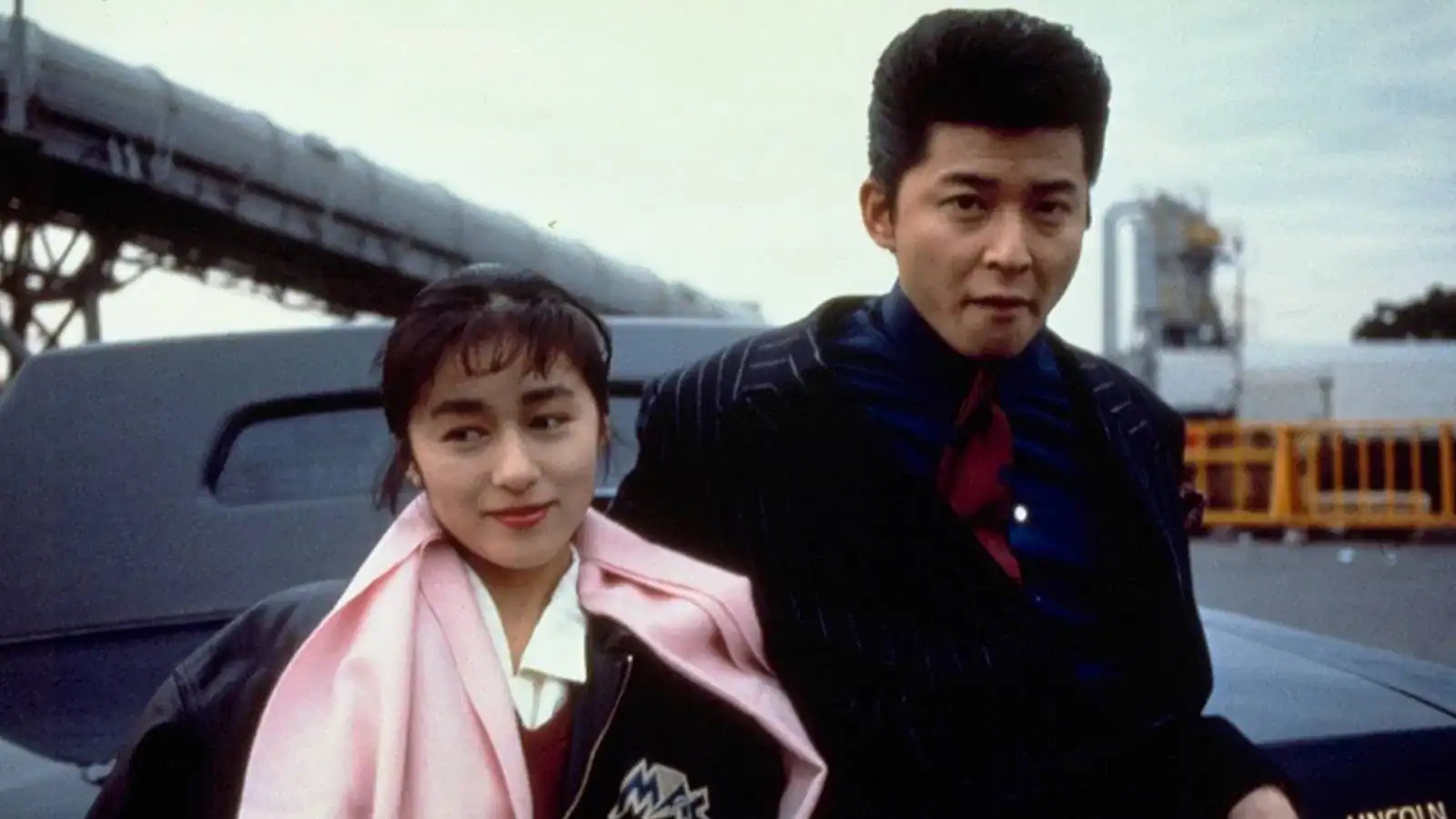

Nikkatsu veteran Yasuharu Hasebe’s V-Cinema noir Danger Point (Danger Point: 地獄への道, Jigoku e no Michi) is a classic tale of nihilistic fatalism in which the bond between the two assassins is tested by the intervention of greed and mystery. Shishido’s Joji is the more old-fashioned of the pair yet fascinated by the mystery behind Sakai’s death, not necessarily wondering if he bears any culpability but confused about why he had to die despite not actually having the missing money. This puts Joji partially at odds with the younger Ken, a more dynamic and less morally ambivalent figure played by the contemporary star Show Aikawa who’d come to represent for V-Cinema what Shishido once had for Nikkatsu action. Together, the chase the various clues they’ve been given looking for the person behind the job and, of course, the missing money.

But the money presents a problem too. Ken begins to wonder if Joji will abandon him and take the prize for himself, though that doesn’t seem to be something that Joji is actively considering. The relationship between the two men is more brotherly than paternal, though Joji does scold Ken for his treatment of Yumi (Nana Okada), the nurse from the hospital and their key witness. He beats and sexually assaults her, though it’s less his lack of chivalry that Joji criticises than the wisdom of bringing a woman into their business. He’s suspicious of Yumi in a way Ken does not seem to be, though they both agree that eventually she’ll have to go before she does them any harm because now she knows too much.

Ultimately, the money turns out to be from a bank job in the Philippines that the American criminals were hoping to convert to US dollars in Japan, though predictably everyone wants the whole amount for themselves, not least Joji and Ken along with the kingpin’s horse-loving girlfriend Saeko (Miyuki Ono) who is playing her own side of the game. Neither Saeko nor Yumi do very well out of this particular affair and are each constrained by the men around them. While Yumi was apparently seduced and abandoned by corrupt cop Sakai, Saeko is hemmed in by her gangster boyfriend Takamura (Hideo Murota) and seeks escape through stealing the money with the help of Sakai, one way or another, at least. Though this world doesn’t seem to want to let either of them have it while the men fight over the spoils in a desperate struggle to assert dominance over the situation.

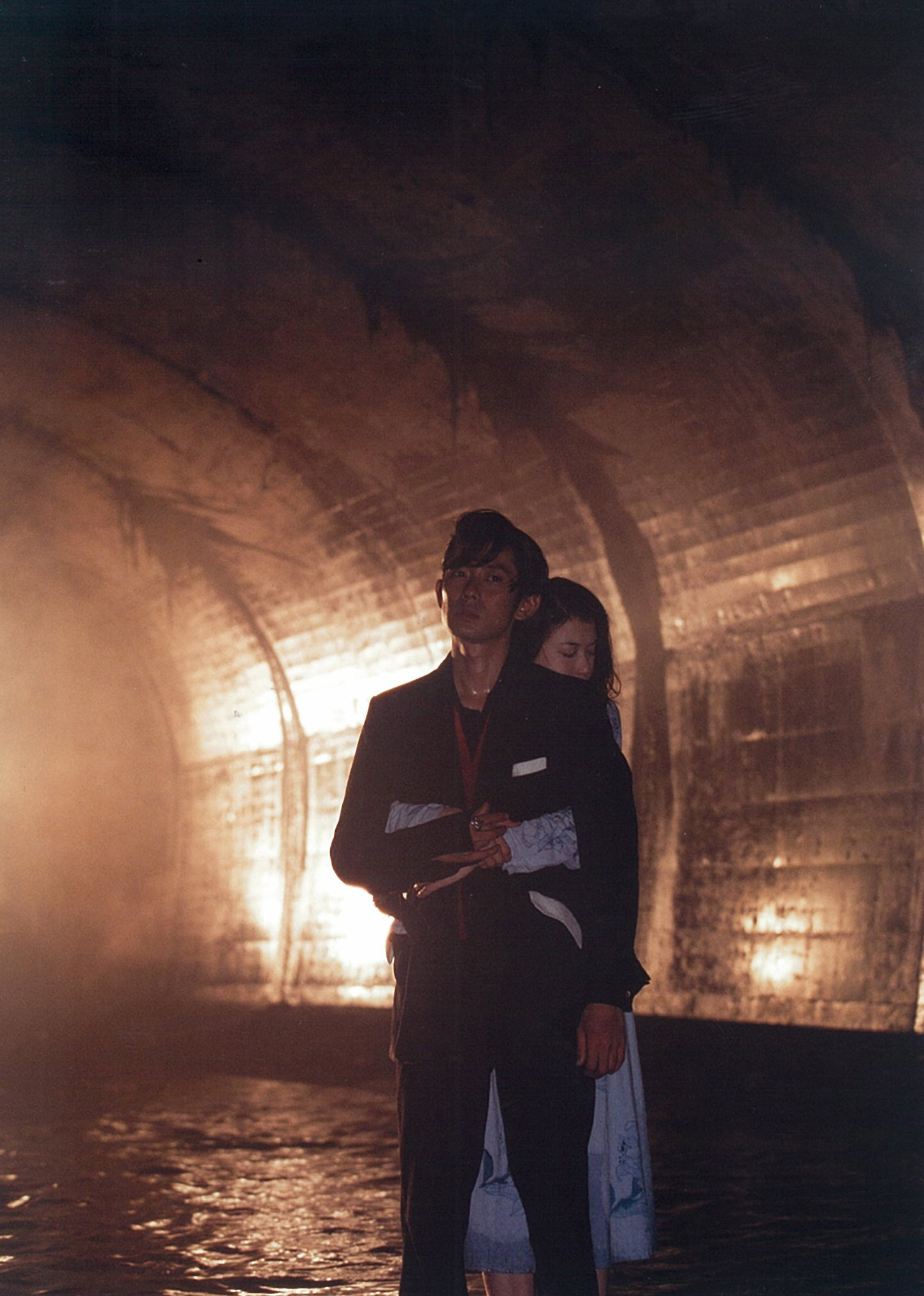

As the ironic “Dead End” sign at the film’s conclusion implies, however, that chasing money is a fool’s errand and leads only to hell. A chase past the no entry signs into an industrial complex suggests that this world is not quite fully formed or in the process of falling apart. The ironic and strangely obvious product placement for Perrier sparkling mineral water might hint at a more sophisticated world the hitmen are on one level trying to inhabit, but in other ways their presence is incongruous. They belong to an earlier time as does this hidden world of bank robberies, smuggled cash, criminal gangs and fixers that seem out of place amid the tail end of the Bubble era. Or in that sense at least, perhaps it’s Japan heading for a crash desperately chasing the riches that seem only slightly out of reach. Nevertheless, there’s a genuine sense of mystery that leads Ken and Joji to their final destination in which they discover that it might not be greed that does for them after all, but in an odd way, love. Their desire for togetherness and fear of separation in the end can have only one conclusion and as much as it is the money that leads them to their doom, it’s loneliness and brotherhood that eventually seal their fate.