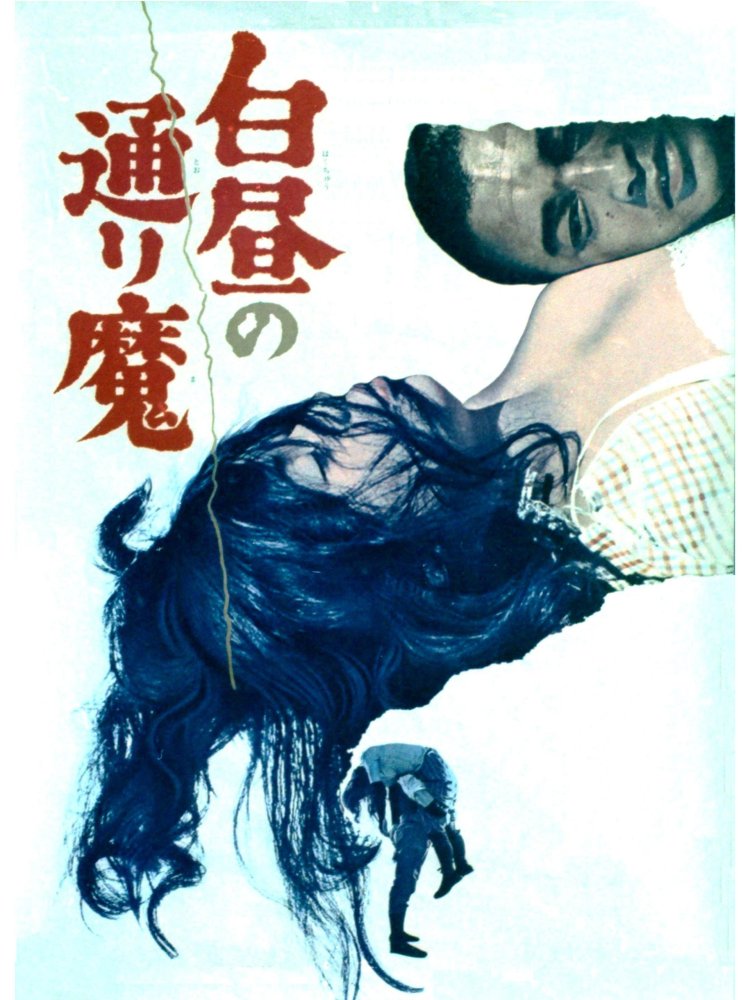

The youth of Japan can’t get no satisfaction in Nagisa Oshima’s 1967 absurdist odyssey Japanese Summer: Double Suicide (無理心中日本の夏, Muri Shinju: Nihon no Natsu). A liberated woman craves sexual pleasure but can find no man willing to satisfy her, so obsessed are they with their solipsistic concerns of death, violence, and the search for self knowledge. The nymphomaniac and disillusioned warrior yearning for a death that will restore his sense of self meet on an empty highway only to wander on aimlessly until reaching their mutually “satisfying” yet inevitable conclusion.

The youth of Japan can’t get no satisfaction in Nagisa Oshima’s 1967 absurdist odyssey Japanese Summer: Double Suicide (無理心中日本の夏, Muri Shinju: Nihon no Natsu). A liberated woman craves sexual pleasure but can find no man willing to satisfy her, so obsessed are they with their solipsistic concerns of death, violence, and the search for self knowledge. The nymphomaniac and disillusioned warrior yearning for a death that will restore his sense of self meet on an empty highway only to wander on aimlessly until reaching their mutually “satisfying” yet inevitable conclusion.

Nejiko (Keiko Sakurai), a sexually frustrated teenage woman, watches some municipal workers scrub at the word Japan graffitied on a bathroom wall but takes off when she realises no one here is going to give her what she wants. Throwing her underwear off a bridge in a symbolic act of abandon she catches sight of naked swimmers trailing a Japanese flag before running into collections of marching soldiers and chanting monks. She takes up with a deserter, Otoko (Kei Sato), who is on a quest for death though his desire is not so much for the act of non-existence as it is for self knowledge. He does not want to kill himself, but to be killed by another person in whose eyes he will see himself reflected and, in his final moments, reach a realisation of everything he is.

After wandering arid, sunbaked deserts the pair are picked up by a mysterious paramilitary group who keep them prisoner in a kind of bunker where they eventually meet a gun crazed teen who just wants to kill, a middle-aged man who gets his kicks through the penetrative act of stabbing, and a wise old gangster who knows what it is to carry the weight of a weapon of death. Meanwhile, once a vengeful guy with a TV turns up, they become aware of a crisis in the outside world involving a rampaging foreigner loose with a rifle on a random shooting spree.

Guns and knives are persistent obsessions. These men are obsessed with phallic objects but indifferent to their phalluses. Nejiko pleads with each of them to satisfy her sexual frustrations but none of them is interested. Her need is for pleasure and relief, seemingly free of social or cultural taboos and born of naturally given freedom. The male urge is, by contrast, destructive – they chase death and violence without pretence or justification. When questioned, one of the bunker henchmen retorts that the situation outside is not war but only killing. All there is is violence without cause or explanation, existing solely because of male destructive impulses.

The situation outside is eerie in the extreme. This is a Japan of silence and emptiness where monks chant on the motorway and shadows people the landscape. Nejiko and Otoko find themselves frequently trying to fit in to human shapes cut into the Earth, finding them far too big or in someway constraining. Yet they also become these shadow figures, birthing new shades of themselves to leave behind as they shed evermore aspects of their essential selves. What caused this situation is not revealed, but everyone seems to be carrying on as normal. There is a crazed killer on the loose and the police have asked civilians to remain in their homes but civilians have ignored them for the most characteristic reasons for uncharacteristic insubordination – they all went to work.

Eventually Nejiko manages to convince some of the men to make love to her, but she remains unsatisfied. Likewise, the teenage “gang member” who wandered into the bunker looking for a gun gets one and succeeds in an act of random killing but discovers that it was not “exciting” after all. Desire is misplaced or its satisfaction unattainable. In this world of pure nihilism there is no pleasure and no relief, no need can be met and no peace brokered. All there is is senseless violence, devoid of meaning or purpose and born of nothing more than a desperation to quell a need which can never be fulfilled.

Death and Eros approach the same end – the “double suicide” of the title though even this is essentially passive and desperate. Youth wanders blindly towards its inevitable conclusion, lacking the will or the strength to fight back. There is no self, there is no higher purpose. All there is is a great expanse of emptiness peopled by shadows, fading slowly from a world gradually falling apart.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Teinosuke Kinugasa maybe best known for his avant-garde masterpiece The page of Madness even if his subsequent work leant towards a more commercial direction. His final film is just as unusual, though perhaps for different reason. In 1966, Kinugasa co-directed The Little Runaway (小さい逃亡者, Chiisai Tobosha) with Russian director Eduard Bocharov in the first of such collaborations ever created. Truth be told, aside from the geographical proximity, the Japan of 1966 could not be more different from its Soviet counterpart as the Eastern block remained mired in the “cold war” while Japan raced ahead towards its very own, capitalist, economic miracle. Perhaps looking at both sides with kind eyes, The Little Runaway has its heart in the right place with its messages of the universality of human goodness and endurance but broadly makes a success of them if failing to disguise the obvious propaganda gloss.

Teinosuke Kinugasa maybe best known for his avant-garde masterpiece The page of Madness even if his subsequent work leant towards a more commercial direction. His final film is just as unusual, though perhaps for different reason. In 1966, Kinugasa co-directed The Little Runaway (小さい逃亡者, Chiisai Tobosha) with Russian director Eduard Bocharov in the first of such collaborations ever created. Truth be told, aside from the geographical proximity, the Japan of 1966 could not be more different from its Soviet counterpart as the Eastern block remained mired in the “cold war” while Japan raced ahead towards its very own, capitalist, economic miracle. Perhaps looking at both sides with kind eyes, The Little Runaway has its heart in the right place with its messages of the universality of human goodness and endurance but broadly makes a success of them if failing to disguise the obvious propaganda gloss.

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate.

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate.

Like most directors of his era, Shohei Imamura began his career in the studio system as a trainee with Shochiku where he also worked as an AD to Yasujiro Ozu on some of his most well known pictures. Ozu’s approach, however, could not be further from Imamura’s in its insistence on order and precision. Finding much more in common with another Shochiku director, Yuzo Kawashima, well known for working class satires, Imamura jumped ship to the newly reformed Nikkatsu where he continued his training until helming his first three pictures in 1958 (Stolen Desire, Nishiginza Station, and Endless Desire). My Second Brother (にあんちゃん, Nianchan), which he directed in 1959, was, like the previous three films, a studio assignment rather than a personal project but is nevertheless an interesting one as it united many of Imamura’s subsequent ongoing concerns.

Like most directors of his era, Shohei Imamura began his career in the studio system as a trainee with Shochiku where he also worked as an AD to Yasujiro Ozu on some of his most well known pictures. Ozu’s approach, however, could not be further from Imamura’s in its insistence on order and precision. Finding much more in common with another Shochiku director, Yuzo Kawashima, well known for working class satires, Imamura jumped ship to the newly reformed Nikkatsu where he continued his training until helming his first three pictures in 1958 (Stolen Desire, Nishiginza Station, and Endless Desire). My Second Brother (にあんちゃん, Nianchan), which he directed in 1959, was, like the previous three films, a studio assignment rather than a personal project but is nevertheless an interesting one as it united many of Imamura’s subsequent ongoing concerns.