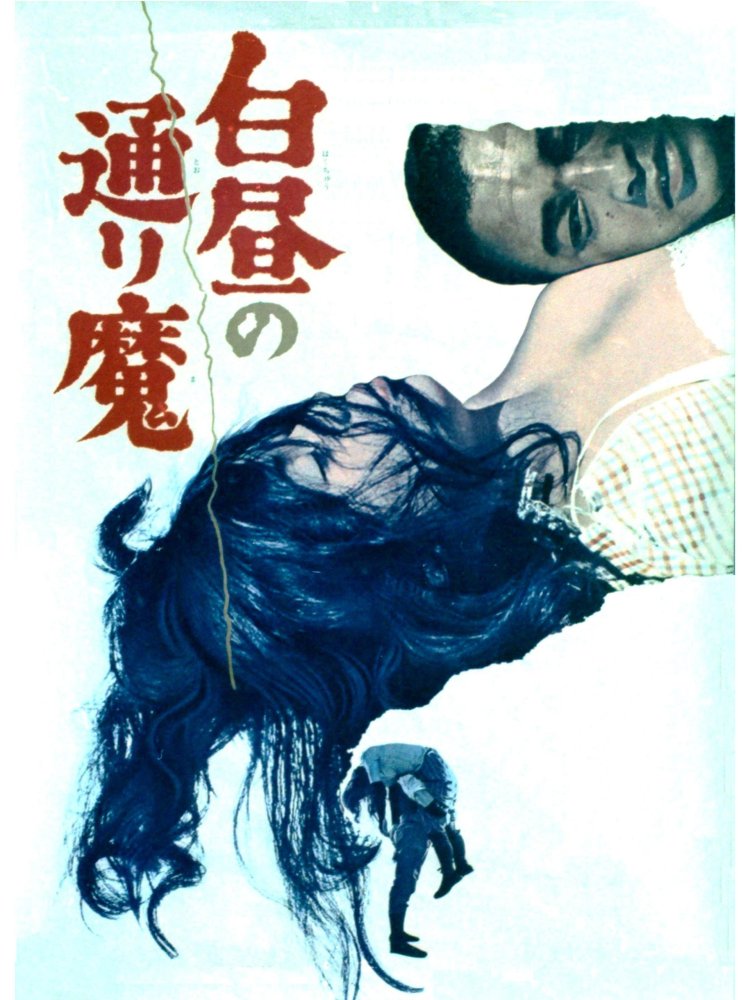

For Nagisa Oshima, the personal is always political and urges for destruction and creation always inextricably linked. Violence at Noon (白昼の通り魔, Hakuchu no Torima), a noticeable shift towards the avant-garde, is a true crime story but the murder here is of idealism, the wilful death of innocence as manifested in the rampage of a disaffected sociopath whose corrupted heart ties together two women who find themselves bound to him in both love and hate. Each feeling responsible yet also that the responsibility for action belongs to someone else, they protect and defend the symbol of their failures, continuing on in despair and self loathing knowing that to turn him in is to accept the death of their idealism in its failure to reform the “demon” that won’t let them go.

For Nagisa Oshima, the personal is always political and urges for destruction and creation always inextricably linked. Violence at Noon (白昼の通り魔, Hakuchu no Torima), a noticeable shift towards the avant-garde, is a true crime story but the murder here is of idealism, the wilful death of innocence as manifested in the rampage of a disaffected sociopath whose corrupted heart ties together two women who find themselves bound to him in both love and hate. Each feeling responsible yet also that the responsibility for action belongs to someone else, they protect and defend the symbol of their failures, continuing on in despair and self loathing knowing that to turn him in is to accept the death of their idealism in its failure to reform the “demon” that won’t let them go.

Bright white gives way to the shadow of a man lurking behind bars. He opens a door and gazes at a woman doing the washing, lingering on her neck before he forces himself in. The woman, Shino (Saeda Kawaguchi) – the maid in this fancy household, knows the man – Eisuke (Kei Sato), a drifter from her home town, but her attempts at kindness are eventually rebuffed when she tells him to go back to his wife and he violently assaults her causing her to pass out at which he point he decides to spare her and murders her employer instead. Rather than explain to the police who Eisuke is, Shino offers only cryptic clues while writing to Eisuke’s wife, Matsuko (Akiko Koyama) – an idealistic schoolteacher, to ask for permission to turn him in and end the reign of terror her husband is currently wreaking as a notorious serial rapist and murderer.

Eisuke, Shino, and Matsuko are all inextricably linked by an incident which occurred in a failing farming collective the previous year. Matsuko, a kind of spiritual leader for the farming community as well as its schoolteacher, preaches a philosophy of absolute love, proclaiming that those who love expect no reward and that through the eyes of love all are equal. Meanwhile, Shino – daughter of a poor family, contemplates suicide along with her father after their lands are ruined by a flash flood and they are left without the means to support themselves. She enters into a loose arrangement with the former son of a village elder, Genji (Rokko Toura), exchanging a loan for sexual favours, later beginning develop something like a relationship with him but one which is essentially empty. Nevertheless when Genji suggested a double suicide she felt compelled to accompany him, only to survive and be “saved” by Eisuke who, believing her to be dead, raped what he assumed was her corpse before planning to dump her body in a nearby river.

It is this original act of transgression that underpins all else. Shino believes herself in someway responsible for Eisuke’s depravity, that his rape of her “corpse” was the trigger for the death of his humanity. Matsuko, meanwhile, sees herself as the embodiment of love – she “loved” Eisuke and thought her love could cure his savage nature and bring him back towards the light and the community. Matsuko was wrong, “love” is not enough and perhaps what she has come to feel for the man who later became her husband on a whim is closer to hate and thereby a total negation of her core philosophy. To admit this fact to herself, to consider that perhaps love and hate are in effect the same thing, is tantamount to a death of the self and so she will not do it. She and Shino are locked in a spiral of inertia and despair. They each feel responsible for Eisuke’s depraved existence, but each also powerless to stop him. Shino in not wishing to overstep another woman’s domain, and Matsuko in being unwilling to admit she has given up on the idea of forgiving the man who has dealt her nothing but cruelty.

Literally seduced by nihilism, Eisuke finally rejects both women. He claims they are responsible – that if Shino had married him instead of attempting double suicide with Genji he might not have “gone astray”, going on to characterise his crimes as “revenge” against his wife’s “hypocrisy”, but then he calmly states that he is the man he is and would always have done these terrible things no matter where and when he was born. Passivity has failed, blind faith in goodness has allowed a monster to arise and those who birthed him remain too mired in solipsistic soul-searching to do their civic duty. Too afraid to let go of their ideals and take decisive action, Shino and Matsuko choose to watch their society burn rather than destroy themselves in an act of personal revolution – Oshima’s thesis is clear and obscure at the same time, “Sometimes cruelty is unavoidable”.

Original trailer (no subtitles, incorrect aspect ratio)

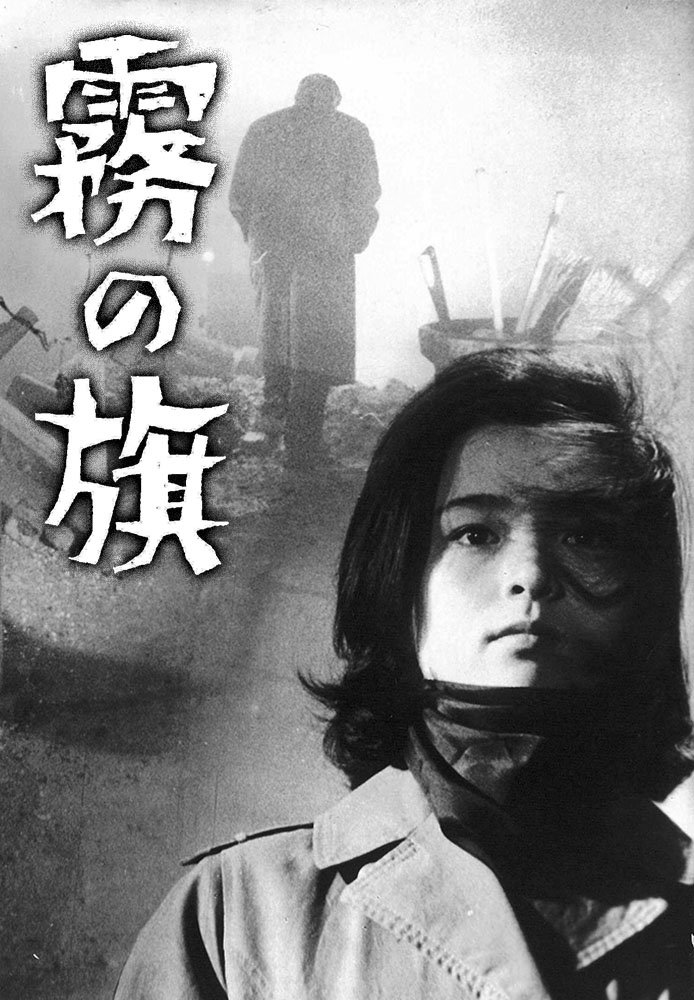

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger.

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger.

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate.

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate. If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story

If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story  Female sexuality often takes centre stage in the work of Kaneto Shindo but in the Iron Crown (鉄輪, Kanawa) it does so quite literally as he refracts a modern tale of marital infidelity through the mirror of ancient Noh theatre. Taking his queue from the Noh play of the same name, Shindo intercuts the story of a contemporary middle aged woman who finds herself betrayed and then abandoned by her selfish husband with the supernaturally tinged tale of a woman going mad in the Heian era.

Female sexuality often takes centre stage in the work of Kaneto Shindo but in the Iron Crown (鉄輪, Kanawa) it does so quite literally as he refracts a modern tale of marital infidelity through the mirror of ancient Noh theatre. Taking his queue from the Noh play of the same name, Shindo intercuts the story of a contemporary middle aged woman who finds herself betrayed and then abandoned by her selfish husband with the supernaturally tinged tale of a woman going mad in the Heian era.

Never one to take his foot off the accelerator, Yazuso Masumura hurtles headlong into the realms of surreal horror with 1969’s Blind Beast (盲獣, Moju). Based on a 1930s serialised novel by Japan’s master of eerie horror, Edogawa Rampo, the film has much more in common with the wilfully overwrought, post gothic European arthouse “horror” movies of period than with the Japanese. Dark, surreal and disturbing, Blind Beast is ultimately much more than the sum of its parts.

Never one to take his foot off the accelerator, Yazuso Masumura hurtles headlong into the realms of surreal horror with 1969’s Blind Beast (盲獣, Moju). Based on a 1930s serialised novel by Japan’s master of eerie horror, Edogawa Rampo, the film has much more in common with the wilfully overwrought, post gothic European arthouse “horror” movies of period than with the Japanese. Dark, surreal and disturbing, Blind Beast is ultimately much more than the sum of its parts. Irezumi (刺青) is one of three films completed by the always prolific Yasuzo Masumura in 1966 alone and, though it stars frequent collaborator Ayako Wakao, couldn’t be more different than the actresses’ other performance for the director that year, the wartime drama

Irezumi (刺青) is one of three films completed by the always prolific Yasuzo Masumura in 1966 alone and, though it stars frequent collaborator Ayako Wakao, couldn’t be more different than the actresses’ other performance for the director that year, the wartime drama