Many things were changing in the Japan of 1957. In terms of cinema, a short lived series of films known as the “Sun Tribe” movement had provoked widespread social panic about rowdy Westernised youth. Inspired by the novels of Shintaro Ishihara (later a right-leaning mayor of Tokyo), the movement proved so provocative that it had to be halted after three films such was the public outcry at the outrageous depictions of privileged young people indulging in promiscuous sex, drugs, alcohol, and above all total apathy – frivolous lives frittered away on self destructive pleasures. The Sun Tribe movies had perhaps gone too far becoming an easy source of parody, though the studio that engineered them, Nikkatsu, largely continued in a similar vein making stories of youth gone wild their stock in trade.

Many things were changing in the Japan of 1957. In terms of cinema, a short lived series of films known as the “Sun Tribe” movement had provoked widespread social panic about rowdy Westernised youth. Inspired by the novels of Shintaro Ishihara (later a right-leaning mayor of Tokyo), the movement proved so provocative that it had to be halted after three films such was the public outcry at the outrageous depictions of privileged young people indulging in promiscuous sex, drugs, alcohol, and above all total apathy – frivolous lives frittered away on self destructive pleasures. The Sun Tribe movies had perhaps gone too far becoming an easy source of parody, though the studio that engineered them, Nikkatsu, largely continued in a similar vein making stories of youth gone wild their stock in trade.

Yuzo Kawashima, a generation older than the Sun Tribe boys and girls, attempts to subvert the moral outrage by reframing the hysteria as a ribald rakugo story set in the last period of intense cultural crisis – the “Bakumatsu” era, which is to say the period between the great black ships which forcibly re-opened Japan to the outside world, and the fall of the Shogunate. The title, Bakumatsu Taiyoden (幕末太陽傳), literally means “legend of the sun (tribe) in the Bakumatsu era”, and, Kawashima seems to suggest, perhaps things now aren’t really so different from 100 years earlier. Kawashima deliberately casts Nikkatsu’s A-list matinee idols – in particular Yujiro Ishihara (the brother of Shintaro and the face of the movement), but also Akira Kobayashi and familiar supporting face Hideaki Nitani, all actors generally featured in contemporary dramas and rarely in kimono. Rather than the rather stately acting style of the period drama, Kawashima allows his youthful cast to act the way they usually would – post-war youth in the closing days of the shogunate.

They are, however, not quite the main draw. Well known comedian and rakugo performer Frankie Sakai anchors the tale as a genial chancer, a dishonest but kindly man whose roguish charm makes him an endearing (if sometimes infuriating) character. After a post-modern opening depicting contemporary Shinagawa – a faded red light district now on its way out following the introduction of anti-prostitution legislation enacted under the American occupation, Kawashima takes us back to the Shinagawa of 1862 when business was, if not exactly booming, at least ticking along.

Nicknamed “The Grifter”, Saiheiji (Frankie Sakai) has picked up a rare watch dropped by a samurai on his way to plot revolution and retired to a geisha house for a night of debauchery he has no intention of actually paying for. Though he keeps assuring the owners that he will pay “later” when other friends turn up with the money, he is eventually revealed to be a con-man and a charlatan but offers to work off his debt by doing odd jobs around the inn. Strangely enough Saiheiji is actually a cheerful little worker and busily gets on with the job, gradually endearing himself to all at the brothel with his ability for scheming which often gets them out of sticky situations ranging from fake ghosts to customers who won’t leave.

Saiheiji eventually gets himself involved with a shady group of samurai led by Shinshaku Takasugi (Yujiro Ishihara) – a real life figure of the Bakumatsu rebellion. Like their Sun Tribe equivalents these young men are angry about “the humiliating American treaty”, but their anger seems to be imbued with purpose albeit a destructive one as they commit to burning down the recently completed “Foreign Quarter” as an act of protest-cum-terrorism. The Bakumatsu rebels are torn over the best path for future – they’ve seen what happened in China, and they fear a weak Japan will soon be torn up and devoured by European empire builders. Some think rapid Westernisation is the answer – fight fire with fire, others think showing the foreigners who’s boss is a better option (or even just expelling them all so everything goes back to “normal”). America, just as in the contemporary world, is the existential threat to the Japanese notion of Japaneseness – these young samurai are opposed to cultural colonisation, but their great grandchildren have perhaps swung the other way, drunk on new freedoms and bopping away to rock n roll wearing denim and drinking Coca Cola. They too resent American imperialism (increasingly as history would prove), but their rebellions lack focus or intent, their anger without purpose or aim.

Kawashima’s opening crawl directly references the anti-prostitution law enacted by the American occupying forces – an imposition of Western notions of “morality” onto “traditional” Japanese culture. In a round about way, the film suggests that all of this youthful rebellion is perhaps provoked by the sexual frustration of young men now that the safe and legal sex trade is no longer available to them – echoing the often used defence of the sex trade that it keeps “decent” women, and society at large, safe. Then again, the sex trade of the Bakumatsu era is as unpleasant as it’s always been even if the familiar enough problems are played for laughs – the warring geisha, the prostitute driven in desperation to double suicide, the young woman about to be sold into prostitution against her will in payment of an irresponsible father’s debt, etc. One geisha has signed engagement promises with almost all her clients – it keeps the punters happy and most of them are meaningless anyway. As she says, deception is her business – whatever the men might say about it, it’s a game they are willingly playing, buying affection and then seeming hurt to realise that affection is necessarily false and conditional on payment of the bill.

Playing it for laughs is, however, Kawashima’s main aim – asking small questions with a wry smile as Saiheiji goes about his shady schemes with a cleverness that’s more cheeky than malicious. He warns people they shouldn’t trust him, but in the end they always can because despite his shady surface his heart is in the right place. Warned he’ll go to hell if he keeps on lying his way though life, Saiheiji laughs, exclaims to hell with that – he’s his own life to live, and so he gleefully runs away from the Bakumatsu chaos into the unseen future.

Masters of Cinema release trailer (English subtitles)

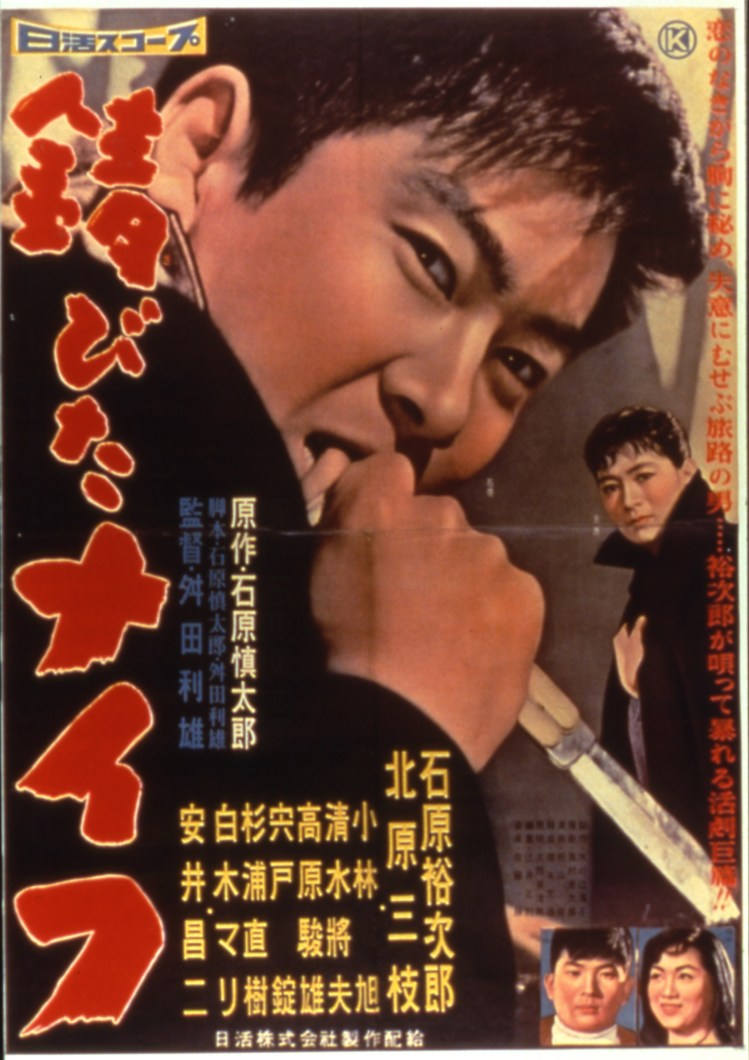

Post-war Japan was in a precarious place but by the mid-1950s, things were beginning to pick up. Unfortunately, this involved picking up a few bad habits too – namely, crime. The yakuza, as far as the movies went, were largely a pre-war affair – noble gangsters who had inherited the codes of samurai honour and were (nominally) committed to protecting the little guy. The first of many collaborations between up and coming director Toshio Masuda and the poster boy for alienated youth, Yujiro Ishihara, Rusty Knife (錆びたナイフ, Sabita Knife) shows us the other kind of movie mobster – the one that would stick for years to come. These petty thugs have no honour and are symptomatic parasites of Japan’s rapidly recovering economy, subverting the desperation of the immediate post-war era and turning it into a nihilistic struggle for total freedom from both laws and morals.

Post-war Japan was in a precarious place but by the mid-1950s, things were beginning to pick up. Unfortunately, this involved picking up a few bad habits too – namely, crime. The yakuza, as far as the movies went, were largely a pre-war affair – noble gangsters who had inherited the codes of samurai honour and were (nominally) committed to protecting the little guy. The first of many collaborations between up and coming director Toshio Masuda and the poster boy for alienated youth, Yujiro Ishihara, Rusty Knife (錆びたナイフ, Sabita Knife) shows us the other kind of movie mobster – the one that would stick for years to come. These petty thugs have no honour and are symptomatic parasites of Japan’s rapidly recovering economy, subverting the desperation of the immediate post-war era and turning it into a nihilistic struggle for total freedom from both laws and morals.

In the extreme turbulence of the immediate post-war period, it’s not surprising that Japan looked back to the last time it was confronted with such confusion and upheaval for clues as to how to move forward from its current state of shocked inertia. The heroine of Shiro Toyoda’s adaptation of the

In the extreme turbulence of the immediate post-war period, it’s not surprising that Japan looked back to the last time it was confronted with such confusion and upheaval for clues as to how to move forward from its current state of shocked inertia. The heroine of Shiro Toyoda’s adaptation of the

Where there’s danger, there’s money! Or, maybe just danger, who knows but whatever it is, it certainly doesn’t lack for excitement. Ko Nakahira is best known for his first feature, Crazed Fruit, the youthful romantic drama ending in speed boat murder which ushered in the Sun Tribe era. Though he later tried to make a return to more artistic efforts, it’s Nakahira’s freewheeling Nikkatsu crime movies that have continued to capture the hearts of audience members. Danger Pays (AKA Danger Paws, 危いことなら銭になる, Yabai Koto Nara Zeni ni Naru) is among the best of them with its cartoon-like, absurd crime caper world filled with bumbling crooks and ridiculous setups.

Where there’s danger, there’s money! Or, maybe just danger, who knows but whatever it is, it certainly doesn’t lack for excitement. Ko Nakahira is best known for his first feature, Crazed Fruit, the youthful romantic drama ending in speed boat murder which ushered in the Sun Tribe era. Though he later tried to make a return to more artistic efforts, it’s Nakahira’s freewheeling Nikkatsu crime movies that have continued to capture the hearts of audience members. Danger Pays (AKA Danger Paws, 危いことなら銭になる, Yabai Koto Nara Zeni ni Naru) is among the best of them with its cartoon-like, absurd crime caper world filled with bumbling crooks and ridiculous setups. So, as it turns out the end of

So, as it turns out the end of