Kon Ichikawa’s approach to critiquing his society was often laced with a delicious slice of biting irony but he puts sarcasm to one side for this all too rare attempt to address the uncomfortable subject of Japan’s hidden underclass – the burakumin. The term itself simply means “people who live in hamlets” but from feudal times onwards it came to denote the kinds of people with whom others did not want to associate – notably those whose occupations dealt in some way with death from executioners and undertakers, to butchers and leatherworkers. Though outright discrimination against such people was outlawed during the Meiji restoration, social stigma and informal harassment remained common with some lingering tendency remaining even today.

Kon Ichikawa’s approach to critiquing his society was often laced with a delicious slice of biting irony but he puts sarcasm to one side for this all too rare attempt to address the uncomfortable subject of Japan’s hidden underclass – the burakumin. The term itself simply means “people who live in hamlets” but from feudal times onwards it came to denote the kinds of people with whom others did not want to associate – notably those whose occupations dealt in some way with death from executioners and undertakers, to butchers and leatherworkers. Though outright discrimination against such people was outlawed during the Meiji restoration, social stigma and informal harassment remained common with some lingering tendency remaining even today.

The Outcast (破戒, Hakai), adapted from the book by Toson Shimazaki (known as The Broken Commandment in English) is the story of a young man of burakumin lineage who has to hide his true identity in order to live a normal life in the Japan of 1904. Segawa’s father, formerly a village elder, sent his son away to live with his brother and his wife in a distant town where they could better hide their burakumin status to enjoy a better standard of life. Sadly, Segawa’s father dies after being trampled by a recalcitrant bull never seeing his son again and leaving him with the solemn commandment to live as a regular person, never revealing his connection with the burakumin world.

This debt to his father’s sacrifice creates a conflict in the heart of the young and idealistic Segawa (Raizo Ichikawa). Forced to listen to the casual racism all around him and unable to offer any kind of resistance, Segawa has become interested in the writings of a polemical political figure, Rentaro Inoko (Rentaro Mikuni), who has begun to write passionate political treatises advocating for burakumin rights. When Inoko turns up in Segawa’s town, he finds himself a new father figure and political mentor but continues to feel constrained by the debt of honour to his father’s sacrifice and is unable to confess his own burakumin heritage even to Inoko.

The world Segawa lives in is a conservative and stratified one in which old superstitions hold true even whilst hypocritical authorities use and abuse the trust placed in them. Inoko falls foul of local politics after he discovers a politician has married a wealthy burakumin woman solely for her money and is planning to expose him at a political rally. This same politician has already threatened to blackmail Segawa who continues to deny all knowledge of any burakumin related activities whilst failing to quell the eventual gossip surrounding Segawa’s lineage. The gossip causes problems at the school where Segawa had held a prestigious teaching position as the headmaster and school board fear the reaction of the parents. Though the people at the temple where Segawa takes refuge after growing tired of the racist inn owners in town are broadly supportive of the burakumin, the priest there has his own problems after having made a clumsy pass at his adopted daughter, Shio (Shiho Fujimura) – the daughter of a drunken teacher sacked by the school in order to avoid paying him a proper pension. At every turn the forces of authority are universally corrupt, selfish and venal, leaving no safe direction for a possible revolution of social justice to begin.

This is Segawa’s central conflict. After his experiences with Inoko, Segawa begins to want to follow in his footsteps, living out and proud as a burakumin and full time activist for burakumin rights. However, this would be undoing everything for which his father sacrificed so much. Talking things over with Inoko’s non-burakumin wife, Segawa is also presented with a third way – reveal his burakumin heritage and attempt to live honestly as an ordinary person, changing hearts and minds simply through leading a life among many other lives. This option seems attractive, especially as Segawa has fallen in love and would like to lead an ordinary life with a wife and family, but his youthful idealism is hungry for a greater, faster change than the one which will be born through simple integration. Despite the warnings of Inoko’s wife who believes change will occur not through activism but through the passage of time, Segawa decides his future lies in advancing the burakumin cause in the wider world.

When Segawa does choose to reveal himself, he finds that there is far more sympathy and support than he would ever have expected. A woman he has come to love wants to stay by his side, his previously hostile friend rethinks his entire approach to life and apologises, and even the children in his class convince their parents that their teacher is a good and a kind man regardless of whatever arbitrary social distinction may have been passed to him through an accident of birth. Segawa’s conflicted soul speaks not only for the burakumin but for all hidden and oppressed peoples who have been forced to keep a side of themselves entirely secret, faced with either living a lie in the mainstream world or being confined to life within their own community. His choice is one of either capitulation and collaboration, or resistance which amounts to a sacrifice of his own potential happiness in the hope that it will bring about liberation for other similarly oppressed people.

Scripted again by Natto Wada, The Outcast takes a slightly clumsy, didactic approach filled with long, theatrical speeches but does ultimately prove moving and inspiring in advocating for the fair treatment of these long maligned people as well as others facing similar discrimination in an unforgiving world. As a treatise on identity and rigid social attitudes, the film has lost none of its power or urgency even forty years later in a world in which progress has undoubtedly been made even if there are still distances to go.

Japanese cinema has its fare share of ghosts. From Ugetsu to Ringu, scorned women have emerged from wells and creepy, fog hidden mansions bearing grudges since time immemorial but departed spirits have generally had very little positive to offer in their post-mortal lives. Twilight: Saga in Sasara (トワイライト ささらさや, Twilight Sasara Saya) is an oddity in more ways than one – firstly in its recently deceased narrator’s comic approach to his sad life story, and secondly in its partial rejection of the tearjerking melodrama usually common to its genre.

Japanese cinema has its fare share of ghosts. From Ugetsu to Ringu, scorned women have emerged from wells and creepy, fog hidden mansions bearing grudges since time immemorial but departed spirits have generally had very little positive to offer in their post-mortal lives. Twilight: Saga in Sasara (トワイライト ささらさや, Twilight Sasara Saya) is an oddity in more ways than one – firstly in its recently deceased narrator’s comic approach to his sad life story, and secondly in its partial rejection of the tearjerking melodrama usually common to its genre.

Haruki Kadokawa dominated much of mainstream 1980s cinema with his all encompassing media empire perpetuated by a constant cycle of movies, books, and songs all used to sell the other. 1984’s Someday, Someone Will be Killed (いつか誰かが殺される, Itsuka Dareka ga Korosareru) is another in this familiar pattern adapting the Kadokawa teen novel by Jiro Akagawa and starring lesser idol Noriko Watanabe in one of her rare leading performances in which she also sings the similarly titled theme song. The third film from Korean/Japanese director Yoichi Sai, Someday, Someone Will be Killed is an impressive mix of everything which makes the world Kadokawa idol movies so enticing as the heroine finds herself unexpectedly at the centre of an ongoing international conspiracy protected only by a selection of underground drop outs but faces her adversity with typical perkiness and determination safe in the knowledge that nothing really all that bad is going to happen.

Haruki Kadokawa dominated much of mainstream 1980s cinema with his all encompassing media empire perpetuated by a constant cycle of movies, books, and songs all used to sell the other. 1984’s Someday, Someone Will be Killed (いつか誰かが殺される, Itsuka Dareka ga Korosareru) is another in this familiar pattern adapting the Kadokawa teen novel by Jiro Akagawa and starring lesser idol Noriko Watanabe in one of her rare leading performances in which she also sings the similarly titled theme song. The third film from Korean/Japanese director Yoichi Sai, Someday, Someone Will be Killed is an impressive mix of everything which makes the world Kadokawa idol movies so enticing as the heroine finds herself unexpectedly at the centre of an ongoing international conspiracy protected only by a selection of underground drop outs but faces her adversity with typical perkiness and determination safe in the knowledge that nothing really all that bad is going to happen. When everything goes wrong you go home, but Yuriko, the protagonist of Yuki Tanada’s adaptation of Yuki Ibuki’s novel might feel justified in wondering if she’s made a series of huge mistakes considering the strange situation she now finds herself in. Far from the schmaltzy cooking movie the title might suggest, Mourning Recipe (四十九日のレシピ, Shijuukunichi no Recipe) is a trail of breadcrumbs left by the recently deceased family matriarch, still thinking of others before herself as she tries to help everyone move on after she is no longer there to guide them. Approaching the often difficult circumstances with her characteristic warmth and compassion, Tanada takes what could have become a trite treatise on the healing power of grief into a nuanced character study as each of the left behind now has to seek their own path in deciding how to live the rest of their lives.

When everything goes wrong you go home, but Yuriko, the protagonist of Yuki Tanada’s adaptation of Yuki Ibuki’s novel might feel justified in wondering if she’s made a series of huge mistakes considering the strange situation she now finds herself in. Far from the schmaltzy cooking movie the title might suggest, Mourning Recipe (四十九日のレシピ, Shijuukunichi no Recipe) is a trail of breadcrumbs left by the recently deceased family matriarch, still thinking of others before herself as she tries to help everyone move on after she is no longer there to guide them. Approaching the often difficult circumstances with her characteristic warmth and compassion, Tanada takes what could have become a trite treatise on the healing power of grief into a nuanced character study as each of the left behind now has to seek their own path in deciding how to live the rest of their lives. Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

If Nikkatsu Action movies had a ringtone it would probably just be “BANG!” but nevertheless you’ll have to wait more than three rings for the Kaboom! in the admittedly cartoonish slice of typically frivolous B-movie thrills that is 3 Seconds Before Explosion (爆破3秒前, Bakuha 3-byo Mae). Once again based on a novel by Japan’s master of the hard boiled Haruhiko Oyabu, 3 Seconds Before Explosion is among his sillier works though lesser known director Motomu Ida never takes as much delight in making mischief as his studio mate Seijun Suzuki. What he does do is make use of Diamond Guy Akira Kobayashi’s boyish earnestness to keep things running along nicely even if he’s out of the picture for much of the action.

If Nikkatsu Action movies had a ringtone it would probably just be “BANG!” but nevertheless you’ll have to wait more than three rings for the Kaboom! in the admittedly cartoonish slice of typically frivolous B-movie thrills that is 3 Seconds Before Explosion (爆破3秒前, Bakuha 3-byo Mae). Once again based on a novel by Japan’s master of the hard boiled Haruhiko Oyabu, 3 Seconds Before Explosion is among his sillier works though lesser known director Motomu Ida never takes as much delight in making mischief as his studio mate Seijun Suzuki. What he does do is make use of Diamond Guy Akira Kobayashi’s boyish earnestness to keep things running along nicely even if he’s out of the picture for much of the action. Yoichi Higashi has had a long and varied career, deliberately rejecting a particular style or home genre which is one reason he’s never become quite as well known internationally as some of his contemporaries. This slightly anonymous quality serves the veteran director well in his adaptation of Arane Inoue’s novel which takes a long hard look at those living lives of quiet desperation in modern Japan. Though sometimes filled with a strange sense of dread, the world of Someone’s Xylophone (だれかの木琴, Dareka no Mokkin) is a gentle and forgiving one in which people are basically good though driven to the brink by loneliness and disconnection.

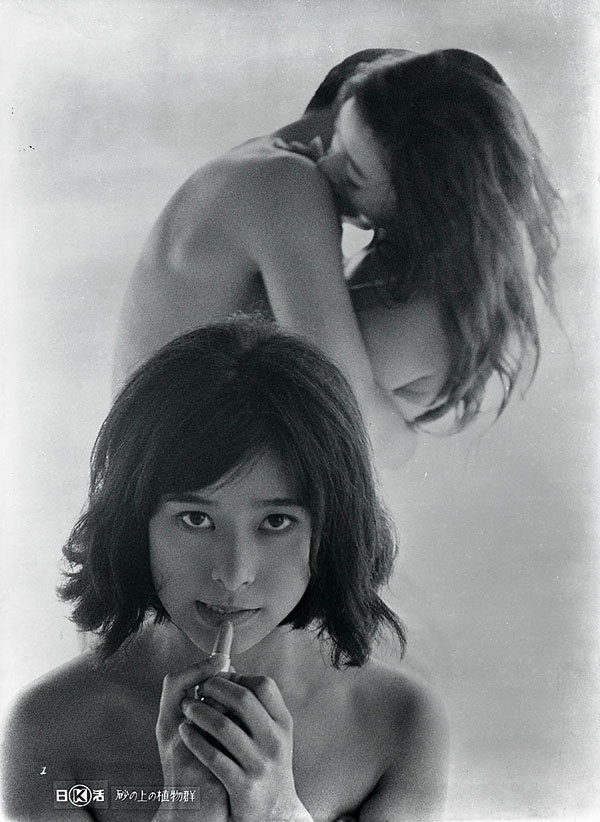

Yoichi Higashi has had a long and varied career, deliberately rejecting a particular style or home genre which is one reason he’s never become quite as well known internationally as some of his contemporaries. This slightly anonymous quality serves the veteran director well in his adaptation of Arane Inoue’s novel which takes a long hard look at those living lives of quiet desperation in modern Japan. Though sometimes filled with a strange sense of dread, the world of Someone’s Xylophone (だれかの木琴, Dareka no Mokkin) is a gentle and forgiving one in which people are basically good though driven to the brink by loneliness and disconnection. Despite being among the directors who helped to usher in what would later be called the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira remains in relative obscurity with only his landmark movie of the Sun Tribe era, Crazed Fruit, widely seen abroad. Like the other directors of his generation Nakahira served his time in the studio system working on impersonal commercial projects but by 1964 which saw the release of another of his most well regarded films Only on Mondays, Nakahira had begun to give free reign to experimentation much to the studio boss’ chagrin. Flora on the Sand (砂の上の植物群, Suna no Ue no Shokubutsu-gun), adapted from the novel by Junnosuke Yoshiyuki, puts an absurd, surreal twist on the oft revisited salaryman midlife crisis as its conflicted hero muses on the legacy of his womanising father while indulging in a strange ménage à trois with two sisters, one of whom to he comes to believe he may also be related to.

Despite being among the directors who helped to usher in what would later be called the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira remains in relative obscurity with only his landmark movie of the Sun Tribe era, Crazed Fruit, widely seen abroad. Like the other directors of his generation Nakahira served his time in the studio system working on impersonal commercial projects but by 1964 which saw the release of another of his most well regarded films Only on Mondays, Nakahira had begun to give free reign to experimentation much to the studio boss’ chagrin. Flora on the Sand (砂の上の植物群, Suna no Ue no Shokubutsu-gun), adapted from the novel by Junnosuke Yoshiyuki, puts an absurd, surreal twist on the oft revisited salaryman midlife crisis as its conflicted hero muses on the legacy of his womanising father while indulging in a strange ménage à trois with two sisters, one of whom to he comes to believe he may also be related to.